The previous parts of this learning series defined key terms related to identity (see What is digital identity – Part 1), and described the digital identity lifecycle (see What is digital identity – Part 2). Let’s turn our attention to three additional topics:

- Canadian laws surrounding personal information

- Digital identity models

- The principle of self-sovereign identity

Digital ID and Privacy

The information contained in digital identity transactions usually involves personal information. Accordingly, privacy measures to protect that information is a cornerstone of digital identity in Canada.

Privacy Acts and PIPEDA

In Canada, the federal government and each province and territory have privacy laws in place that regulate how governments collect, use, and disclose personal information. The Government of Canada, British Columbia, Quebec and Alberta, also have privacy laws in place that regulate how private sector organizations collect, use and disclose personal information. For the Federal Government, these laws are the Privacy Act and the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA).

The Privacy Act addresses how the federal government must handle personal information, and a person’s rights to access and correct their personal information.

PIPEDA establishes the legal obligations of private sector organizations engaged in for-profit activities.

PIPEDA lists 10 fair information principles. These provide the guidelines for personal information protection standards:

- Accountability

- Identifying purpose

- Consent

- Limiting collection

- Limiting use, disclosure, and retention

- Accuracy

- Safeguards

- Openness

- Individual access

- Challenging compliance

These principles dictate that a person should:

- Know what is being asked for and why;

- Have to be asked to consent to the provision and sharing of personal information;

- Know how personal information is used and shared;

- Be assured of the protection of personal information; and

- Be assured that only what is required is being asked for and shared.

The safeguards across these various pieces of privacy legislation apply to all personal information. In the context of digital ID, this personal information is typically an attribute of the credential, like name, phone number, birth date, etc.

The degree to which a person controls their own personal information when it is associated with a credential depends on the way a particular digital identity ecosystem has been designed. There are multiple models in the digital identity space. Each model has its pros and cons. Let’s look at some of the common models for digital identity.

Digital Identity Models

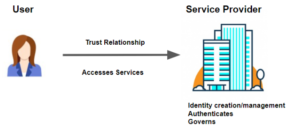

Centralized identity and credentials – in this model, an account is created, controlled, and owned by the organization that a person is transacting with. Examples include creating an online account to purchase goods from an online shop, registering with your province to access health information, or signing up to bank online.

In each case, the organization determines what they need to know about you to issue you a credential (e.g. a username and password) to access their site. In the case of purchasing from an online shop, they might just want to know they have a valid email address and credit card. Who you are likely doesn’t matter. In the case of access to health or banking information the organization will need a lot more certainty that you are who you say you are to make sure that the right personal information is getting to the right person. You might have to go into a physical office when you are first creating your account or pass other types of onboarding steps. Regardless of how much certainty the organization needs, however, what makes this model centralized is that the organization ultimately controls the information you provide to set up the account.

Centralized models were the most practical to put in place when standards and technology were less advanced. However, several issues have emerged:

- The user, by necessity, gives up control over their personal information;

- A single breach can compromise a massive amount of personal information because it is all stored (often in one place) by the organization;

- Multiple single points of failure make the system as a whole less reliable; and

- As a closed system, it does not lend itself well to usage beyond the issuing service provider.

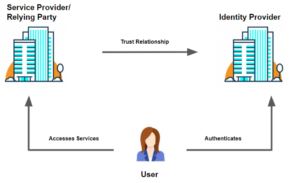

Federated identity – this model enables single sign-on, which opens up the possibility of one digital identity (e.g your banking log-in or social media log-in) being used to access multiple domains. In this model, we see the introduction of an identity provider. An identity (or user account) established and/or managed by one organization is used to access the services of another. One example is using a Sign-In Partner to log into your Canada Revenue Agency account.

Federated identity models have many of the same risks as centralized models. This includes single points of failure, dangers associated with centralized repositories, and relinquishing control of end-user data. There are also new complexities introduced with federation:

- Interoperability and integrations with other systems become expensive and difficult to maintain; and

- The requirement for point-to-point integrations between service providers and verifiers significantly hampers scalability.

However, this model does offer some advantages:

- The opportunity to access multiple services using one digital identity;

- These systems are standards-based with consistent methods for information exchange; and

- While the risk of attack on a centralized digital identity information repository still exists, the identity information is managed by organizations who made a deliberate decision to manage digital identity, meaning they are more likely to have greater levels of security and governance in place to protect that information.

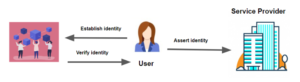

Decentralized identity – this model is user-centric. In this model, a person (the user) creates their digital ID through an onboarding process where they prove that they are who they say they are beyond a reasonable doubt. This could be similar to, for example, the process you go through to get a driver’s licence issued. Once the onboarding process is complete, the user is in control over how that information is shared and with whom. Continuing the driver’s licence example, the issuer (in this case a government) knows that a driver’s licence has been issued to you but once it is issued to you, you are in control. You choose when you show your driver’s licence and to whom. The issuer does not know when and where you have shared it.

This issuing and sharing process is housed on a network. It often leverages blockchain technology using distributed ledgers and cryptography techniques. As a result no centralized database is required.

The distributed ledger technology used in decentralized ID networks enables trust in the network without the control of one central authority. This means:

- There is no central administrator or centralized data storage;

- The identity network is formed by peers that have the same permissions and transact freely with each other;

- Transactions are performed through a consensus mechanism (the agreements between parties on the status of the ledger);

- Public key cryptography allows an appropriate level of security; and

- Data integrity is maintained; which means

- Users are in possession and control of their data; and

- The data is secure.

In the centralized model, the organization delivering service is the sole authority (in our centralized example, this could be a bank). They set the rules, create the identities, set the terms for the management of an identity (within the boundaries of applicable laws). In federated or decentralized models, different entities will be responsible for activities. A credential may be created by one organization. Authentication could be through another security system. Validation might be a third party operation before finally being verified by another entity, with the user’s consent. A common understanding of the governance and operational standards involved is crucial.

Self-Sovereign Identity

Often, self-sovereign and decentralized identity are used synonymously. There are several definitions, with some variances on the governance and technology. We define self-sovereign identity as a method of decentralized identity where the user is in absolute control of sharing and disclosure. For instance, take the example above where a driver’s license is presented at a bar. In this case, the bouncer only needs to confirm that you are of legal drinking age. They do not need to know other information included on the credential, such as your address, eye colour, weight or even your exact birth date. Proving that your age is equal to or greater than the minimum threshold would suffice. In a decentralized model, you may be able to choose who you share your credential with but you may still have to share the full credential. In a self-sovereign model, you can further refine what you share by choosing which attributes you share (e.g. age, birthdate, address etc). This is called selective disclosure. We will get into this further in future publications.

Like any model, the implementation of a self-sovereign identity can vary but there are several common key characteristics that are fundamental. Self-sovereign identity principles deliver several advantages not possible in traditional models:

- Sharing only what is absolutely necessary;

- Improved protection of data integrity;

- Significantly reduced dependence on specific technologies;

- Issuers do not need to integrate with verifiers;

- Issuers do not know when their credentials are being used (transactions remain between the user and verifier);

- No reliance on centralized or third-party authorities for authentication; and

- Significant reduction in the burden of authenticator management.

Looking ahead to future learning

We’ve talked about one of the most important issues affecting the adoption of digital identity: privacy and the protection of personal information. We have also identified some of the key measures in place to help alleviate privacy concerns, such as laws and implementation models.

In future parts of this learning series we will have a closer look at other components of the structure of a digital identity ecosystem. We will look at other factors affecting the adoption of digital identity and ways these are being addressed. Standards and frameworks associated with decentralized identity management are rapidly evolving. Broadly adopted standards are important to ensure all players in the digital identity space can work together. Equally important are the mechanisms to assess compliance with these standards.

We would love to hear from you and address your most popular questions! Get in touch with IDLab!